As violent juvenile crime rocks the headlines, China debates: How young is too young to lock up?

On the evening of October 29, 2020, after dinner and alcohol at a restaurant in the small city of Xingping, Shaanxi province, six teenagers got into a fight with a 15-year-old peer who had allegedly blocked them as contacts on messaging app WeChat. Knocked unconscious, the boy was hidden in a hotel by the gang, wary of drawing attention to their fight. But by morning he was dead.

The brutality of the teenagers’ violence was only exacerbated by their apparent eagerness to cover it up. The panicked culprits buried their victim in a field outside a nearby village, then took his SIM card and posted a photo on the boy’s social media captioned “Off to work!” to give the impression he was still alive. Police found the body nonetheless, and by the following week had taken the six suspects into custody.

The suspects’ ages ranged from 14 to 17, meaning that none of them will face the same punishment an adult would for the same crime. They could, however, face juvenile charges under China’s Criminal Law, which was revised in December 2020 to reduce the age of criminal responsibility for serious crimes (like homicide) from 14 to 12 after a string of shocking juvenile cases hit the Chinese headlines over the past five years.

In May of last year, a 15-year-old from Shandong province strangled her lawyer mother to death, allegedly because she was too strict. In November 2018, six teens aged 14 to 17 from Shaanxi were arrested for forcing a 15-year-old girl into prostitution, then killing her and burying the body. In 2019, a 10-year-old girl was killed by a 13-year-old boy; and in 2015, three students in Hunan gagged and beat their teacher to death in her own home.

This apparent crisis of youth morality and discipline has even influenced popular culture. Last summer, the wildly popular TV series The Bad Kids enraptured audiences with its plot of three children from broken homes who get mixed up in murder, blackmail, and extortion.

According to a report by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate released in June 2020, China prosecuted 61,295 children under 18 in 2019, compared with 58,307 the year before. Between 2014 and 2019 the most common juvenile crimes were burglary and robbery, fighting in public, and “picking quarrels.” Although violent crime has fallen overall in the period, there have been more prosecutions for rape and sexual assault among minors. The vast majority of youth offenders—perhaps over 95 percent—are boys.

But these figures might not tell the whole story, as not all juvenile offenders are prosecuted. The legal system officially favors education over punishment when it comes to minors. Court records show that the number of convicted juveniles actually dropped from 88,891 in 2008 to 35,743 in 2016, but other metrics indicate that violent crimes among youth are on the rise, while the average age of prosecuted youth criminals is falling.

The true state of underage crime in China may be difficult to discern, but in media headlines it is more common than ever. Violent and sensational stories are provoking furious reactions online, leading to calls from law-enforcement and lawyers for stricter consequences for youngsters who break the law.

Zhang Huimin, a public security officer in Ordos, Inner Mongolia, is clear where the blame lies for such shocking acts. “These children’s actions can’t be separated from their parents,” says Zhang, who has worked as a criminal investigator since 2009.

Most of the juvenile cases Zhang deals with are petty acts of fighting or pickpocketing, but nearly all the offenders—rich or poor, rural or urban, locals or migrants—have one thing in common: They lack attention from their parents or guardians. “Most of the kids have extremely bad relationships with their parents, especially with their father,” she says. “Their parents might as well be dead—they take no responsibility for the kids.”

A white paper published by the Beijing No. 1 Intermediate Court in 2017 suggested that lack of parental attention was a factor in the increasing numbers of young offenders they had seen. A study of juvenile detainees in southwestern China found that between 2009 and 2011, over 83 percent of detainees were from rural areas, and two-thirds of those were “left-behind” children with one or both parents working in another city, often leaving them to be raised by their grandparents.

Zhang recalls a 10-year-old thief and serial offender whom her team would bring into the station, and then release, at least three times each year. “He had no chance,” she says. The boy’s mother left after he was born, and his father was an alcoholic. His grandfather, who became the boy’s sole caretaker after his grandmother’s death, was in poor health and never paid attention to what his grandson did. The boy’s crimes escalated from stealing bicycles to joyriding in cars, until he reached the age of responsibility (then 14) and was sent to juvenile prison.

Liu Shuwen (pseudonym), a 29-year-old from Hubei province, was arrested for stealing when he was 17. He blames his economic circumstances for his turn to crime. “If I didn’t steal, I wouldn’t have had any way to live,” he claims. “At 15, no one wanted to hire me, but I didn’t want to go to school, and I didn’t have enough money for vocational college.”

The report by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate stated that 39 percent of juvenile offenders were unemployed, while 22 percent were farmers, and just 8 percent were students. Many offenders are not in school, and don’t receive adequate care and attention at home.

In reducing the age of criminal responsibility, effective as of March of this year, the government conceded to years of increased public outrage as reports periodically emerged of atrocities committed by children under the age of 14 going unpunished.

In March 2018, for example, a 13-year-old boy escaped punishment after he followed a girl into an elevator, attacked her with scissors, forced her to strip naked, and robbed her. The girl’s family could only seek financial compensation from the family of the perpetrator, as he was too young to be charged with the crime. In December that year, a 12-year-old boy from Hunan province, who killed his mother in retaliation for being beaten, was back at school within a week of the crime—despite the protests of the parents of his classmates, who feared for their children’s safety.

Youths between 12 and 18 can now be held partly responsible, with different levels of punishment depending on their age and the seriousness of their offense. Officer Zhang is adamant that the change is for the better: “If this law had been changed earlier, then that 10-year-old boy would have been taken off the streets sooner.”

The original age of 14 for criminal responsibility was set by an amendment to the Criminal Law back in 1997. Many argue this age is no longer appropriate for a society that has changed significantly since. Li Chunsheng, a specialist in minor protection law and a member of the Hubei Lawyers Association, wrote in China Youth Daily in 2018 that “children’s mental maturity has accelerated and many minor offenders show cognitive ability similar to adults.” But there is little scientific evidence for this claim.

Others argue that it is only the sensationalized reporting in the media that has provoked the government to respond, and lowering the age will not have a significant impact on juvenile crime rates. “The statistics I have seen actually show that juvenile crime has been decreasing in recent years…but the number of crimes against children have risen,” argues Zhao Hui, a lawyer and member of the Beijing Children’s Legal Aid and Research Center. “In the last few years some extremely horrific cases have attracted the attention of society, but actually these are only specific cases.”

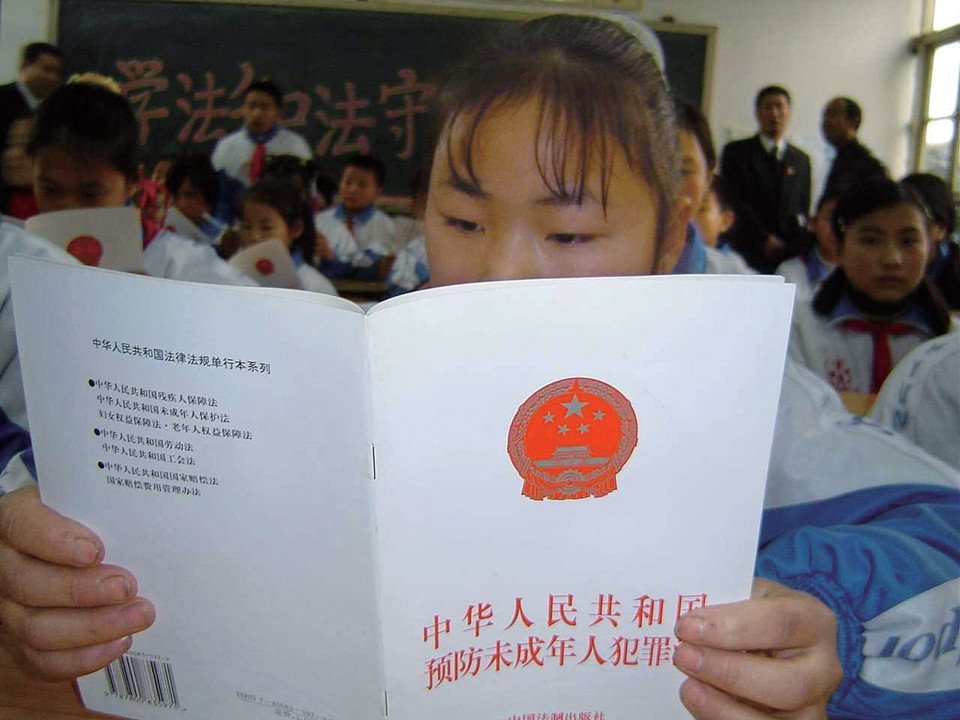

It is not a lack of severity from the law that causes young children to offend, Zhao tells TWOC. “To stop them committing crimes, we need more psychological guidance and education on the law. A lot of children don’t understand the law, and they don’t know that what they’ve done is against the law,” she says. “There isn’t just one thing you can do to help these children; it’s a multi-faceted problem.”

According to the think tank Child Rights International Network, the worldwide median age for criminal responsibility is 14. The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child recommends 12 as the absolute minimum age, but calls for countries to raise their minimum as far as possible. In India, children as young as 7 can be held responsible, while the US sets a minimum age of 11 for federal offenses, though states can also impose their own limits.

China’s youth justice system is still in the process of being reformed. The system is itself juvenile, with the first court for youth criminals established in Shanghai in 1984. China’s Juvenile Protection Law, enacted in 1991, states that education should be the primary means for handling delinquency, with punishment second. If a juvenile case reaches the criminal courts, the offender may be sentenced to administrative detention, legal education, addiction rehabilitation camps, juvenile prisons, or “specialized education schools.”

While the “education first” principle remains, critics argue that lowering the age of criminal responsibility will lead to more incarceration—and less reform—for children. Instead, more resources need to be given to educating youngsters on the law, as well as recognizing that many problems arise because of systematic inequality.

Of the young offenders Zhao sees in her work as a lawyer, she suggests around 70 percent are part of the “floating population” that have migrated to new cities (with or without their parents), or are “left-behind” children. Providing their children with adequate psychological support and education is vital.

The Law on the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency, first enacted in 1999, acknowledges some of these shortcomings with a set of new revisions that will come into effect in June of 2021. The revisions propose a greater role for “special education schools” to rehabilitate young offenders with “seriously bad behavior,” which does not reach the threshold for criminality, and says schools should appoint teachers for mental health education and establish systems to prevent bullying.

Previously known as “work-study schools,” specialized education schools are supposed to teach students about the law and social responsibility, while also teaching them vocational skills. They are often staffed by public security officials and police officers, and model themselves on military training camps with strict management of the students. “From when the students arrive at school at 3 p.m. on Sunday until they leave at 3 p.m. on Friday, every teacher is monitoring them all the time,” Liang Genyu, head teacher of Qide Special Training School in Shanghai, told The Paper in 2016, “including at night when they self-study and sleep in their dorm.”

Qide and other specialized schools claim to mix strong discipline with empathy, offering both practical and academic education to prepare their students to re-enter society. But Liu, who was sent to a work-study school for eight months after his stealing offense, provides a much bleaker picture. “We weren’t given enough food to eat, so of course we would fight…and the school uniforms were ragged and worn,” he says.

Liu saw kids violently beaten by staff as punishment for various behaviors. There was little actual study, and a monotonous daily regime of military training in the morning and farm labor in the afternoon. “It was a dark place,” he recalls.

Until now, enrollment in specialized schools has required the consent of the students’ parents or guardians. The new rules this year will allow courts and law enforcement to mandate children to attend these schools—regardless of parental consent—if their behavior has “seriously endangered society.”

Lawyer Tong Lihua, director at the Beijing Children’s Legal Aid and Research Center, has criticized proposed revisions to the Law on the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency for its lack of targeted solutions for different crimes committed at different ages—for instance, those who commit serious and less serious crimes could be held in the same facility.

In an article published by the Center’s WeChat account in August 2020, Tong also suggested the juvenile justice system needs to focus on prevention, rather than reform or punishment. The power to detain and restrict liberty should be taken away from the police, and given instead to the courts, which can make rational decisions based on the offender’s background and their psychological condition.

Community-based approaches do exist, such as the “help and educate” method, which sends local community organizations to help families with badly behaved children. However, many localities lack the capacity to offer professional behavioral correction and psychological counseling for children who go astray, while social assistance programs typically target families and adults, who are often not present in youth offenders’ lives.

With no family to rely on, and having learned no useful skills, Liu turned to theft once again after leaving the work-study school. “The education inside wasn’t good, so after I came out I still broke the law,” he says. “When I came out, I was already half cut off from society.”

Eventually, after spending three years in jail as an adult, Liu found a job as an air-conditioner salesman. But he is still haunted by his time in the work-study school, and is desperate to provide for his family so his newborn son won’t turn to crime like himself: “I don’t want him to have lost even before he reaches the starting line.”

– Additional reporting by Yang Tingting (杨婷婷)

Illustration by Cai Tao, elements from Shetuwang and VCG

Minor Offense is a story from our issue, “Dawn of the Debt.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.