The Li people of Hainan were at the forefront of Chinese textile development for centuries, and still use traditional methods today

Chinese history buffs may be familiar with the name Huang Daopo, or Madam Huang, a rare example of an ordinary woman who left her mark on history. Born on the mainland near Shanghai in 1245, Huang was sold into marriage by her family at a young age, and forced to work on the family farm of her husband all day and spin cotton all night. Growing tired of her ill treatment, Huang fled and hopped on a boat on the Huangpu River to sail away to freedom, eventually becoming an innovator of China’s late 13th century textile industry. While Huang Daopo is famous for being a textile pioneer in Shanghai, many don’t know that she spent more than 30 years honing her skills with the Li people on Hainan Island.

The Li are celebrated as the leaders of textile technology development in China. Using their tropical surroundings to their advantage, they sourced various fibers from the rainforests and invented new weaving techniques. Along with hemp and cotton, there are over 100 species of plants on the island that can be spun into weaving fibers. The most well-known of the textiles developed by the Li people is the Li brocade (黎锦). The woven fabric has been nicknamed a “living fossil” in Chinese textile history, with the technique still flourishing today.

Prior to the use of hemp and cotton in weaving, the Li people developed methods to process the bark of various plants into a non-woven fabric. The technique is still preserved in some Li villages to this day. As the craft evolved from non-woven fabrics to woven textiles, the Li became some of the first peoples to begin planting, spinning, and weaving cotton. Records show Li cloth-makers putting innovative techniques into practice as far back as 3,000 years ago.

As techniques evolved, different fabrics came into vogue. By the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), “broad cloth” (广幅布) was the most prominent of fabrics. Initially only produced as a tribute to the imperial court, the product flourished and became the favored material for making the fashionable “head-through dress” (贯首衣), a simple piece of cloth with a hole cut in the middle. This traditional style of garment can now be found on display at the Hainan Provincial Museum of Ethnology.

By Huang Daopo’s time, the Li’s cotton textile technology was far more advanced than that of the mainland. Historical records show that some woven products were already being sold by Hainanese to the rest of China. But Huang was the one who brought the advanced textile techniques from Hainan to the mainland.

After escaping from her abusive in-laws, Huang took refuge in a Daoist temple, where she obtained the “Dao” in her nickname. One day, a woman from Hainan came to pray, and Huang was struck by the beautiful clothes she wore. She begged the woman to take her to Hainan to learn the weaving techniques—as well as to get as far from her old life as possible. It was said that Huang lived in Shuinan village in today’s Sanya, and spent the next three decades learning the Li people’s advanced techniques for planting cotton, spinning fibers, and weaving.

Yet Huang—who was well-liked by the local people, and who loved Hainan—still missed her hometown. In 1295, she returned home with all she had learned from Hainan. She taught the people in her hometown everything she knew, and greatly increased the design and efficiency of textile machines. After Huang died in 1330, people named her the “mother of Chinese textile technology.” Hainanese people also never forgot her. In the Yacheng Academy in Sanya, there is a memorial hall for Huang Daopo, where people can pay homage to this ambassador between the Li and Han cultures.

The Li textile techniques are still used today. At Binglanggu, visitors can watch elderly Li women demonstrating their skills. Though machines can produce the same products much more efficiently today, a handmade Li brocade is still the area’s best-selling souvenir. Li textile techniques mainly include four elements: spinning, dyeing, weaving, and embroidery. Threads were originally twisted by hand, and later spun with a rod and spindle, until the creation of the spinning wheel. Li dyes use a variety of plants, and occasionally minerals, to produce stunning colors: blues, greens, and black from leaves; yellow from turmeric; and red and brown from heartwood tree bark boiled with grass or snail ash.

Li embroidery exists in both single-sided and double-sided varieties, usually created on a waist loom, or the more advanced foot loom. The foot loom is very similar to modern loom machinery, and includes a frame with pedals, shafts, and a heddle.

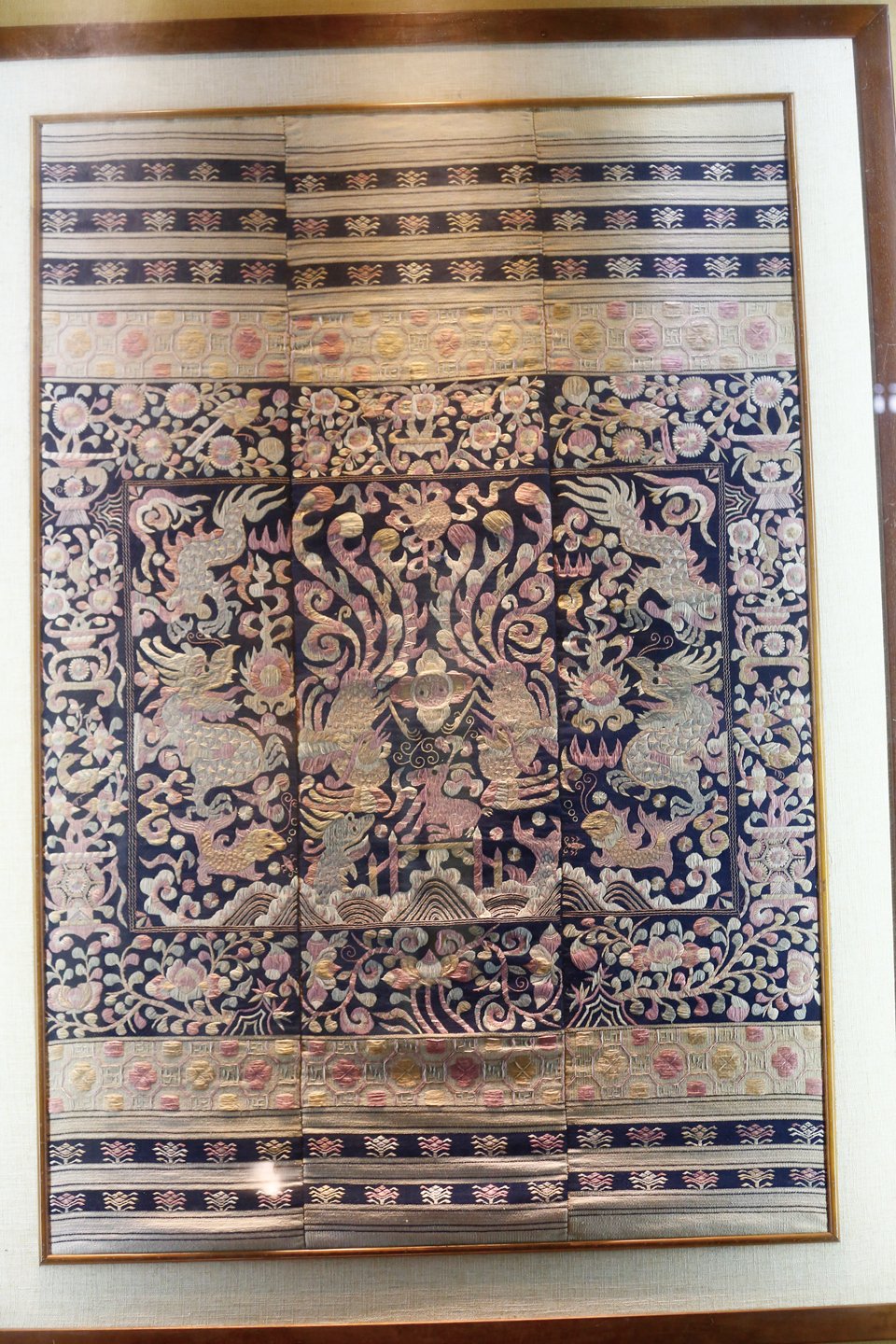

The skills of embroidery evolved from a necessity into a highly valued art form. Thought it was originally used to reinforce fabrics to make them stronger and last longer, the decorative functions of embroidery quickly took center stage, and it even became a method for storytelling, with ancient tales depicted on intricate tapestries hung on walls.

As we look at these ornate and meticulous designs, it is hard to believe they were created using technology thousands of years old. The designs of the Li embroidery are diverse and complex, often depicting creatures from mythology, deities, and daily life, as well as precise mosaics and geometric patterns.

Over the last 20 years, traditional textile culture in Hainan has been on the receiving end of worldwide attention and honors from China’s Ministry of Culture, the State Council, and UNESCO. A visit to Hainan is definitely not complete without an exploration of this precious historical art form.

All photographs by Zhong Ming

Excerpt taken from Hainan: Jade Cliffs to Ocean Paradise, TWOC’s new guide to China’s southernmost province. Get your copy today from our WeChat store!