Hainan cuisine is rich in flavor and history

The earliest mainland settlers on Hainan, who were fed by the fertile farmlands of the Yangtze and Yellow River valleys, wrote less-than-flatteringly about the agricultural offerings of the shallow, windswept shores they landed on. “Hainan has not seen a harvest in years and is lacking in all food,” the exiled poet Su Shi (苏轼)—also known under the pen name Dongpo (东坡)—bluntly stated in a letter to his great-nephew in 1099.

“The ships from the ports of Quanzhou and Guangzhou never come, and there is no medicine or sauce; one must make do in such impoverished surroundings,” Su continued. In an essay, he lamented that the indigenous diet mainly consisted of yams grown in the nutrient-poor soil, raw honey, and rodents such as bats and rats.

Yet few of these pampered mainlanders ventured into Hainan’s mountainous and forested interior, which, though nominally under control of the central Chinese empire, was assiduously defended by the Li people. In their semi-autonomous lands, this indigenous population enjoyed an ecological diet that embraced the biodiversity of the island’s flora and fauna. Their unique, free-range farming method was encapsulated by a folk saying: “Fish that swim in the stream, chicken that sleep in trees, and cows that never come home.”

Even Su was eventually charmed. The well-known foodie, credited with inventions like the fatty, flavor-rich Dongpo pork, was moved to create a few dishes with a distinctly Hainanese spin during his three-year stay on the island. His “vegetable stew” called for picking a number of local herbs straight from the ground and washing them in the island’s pristine streams. The leaves are then fried with just enough oil that their natural fragrance oozes into the gravy. He also substituted local yams in a recipe for corn stew allegedly learned from his father, and boasted of the result in a poem: “Pure white, and fragrant as ambergris/ A flavor as fresh as milk/ Smoother than minced sea bass with ginger/ Is Dongpo’s corn stew.”

Seafood was another novelty for the dislocated literatus. According to his writings, shortly before the Winter Solstice of 1099, local fishermen gifted Su and his son with a bundle of oysters, some of which they ate after boiling in a sauce of rice wine, and others straight out of the shell after barbecuing. “Don’t let the officials in the north know of the delight of eating oysters, or they will all try to get themselves exiled to Hainan,” Su told his son, and called his meal “a gastronomic pleasure as I have never before experienced.” Today, the Dongpo Academy in the city of Danzhou still serves a version of both the poet’s corn stew and wine sauce oysters.

It was quite a stunning turnaround from his bleak early reports home, and a perfect testament to the magic of the island’s food culture—transforming the simplest elements from nature into feasts, and a homesick northern exile into a fan.

Culinary Melting Pot

As Su discovered first-hand, diversity and cultural exchange have been the bywords of Hainan’s culinary history. The aboriginal Li people, who hunted, fished, and grew yams and a grain called “mountain millet” in Hainan’s dry soil since prehistoric times, adopted paddy farming from the mainland armies and settlers starting from the third century CE. In turn, the predominantly Han Chinese newcomers incorporated native plants and fruits into their menus: frying pineapple with meat, dipping mango slices in chili sauce, and cooking assorted foods in the juice, milk, and oil of coconuts.

During the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644), mercenaries of the Miao ethnicity were resettled from the Guangxi region to Hainan, becoming the island’s second biggest ethnic minority group. These new migrants left their biggest culinary mark on Hainan in the form of pickled vegetables and sauces, popularizing the sour and spicy tastes found today in dishes like Lingshui sour rice noodles and Miao sour fish soup. Dishes of Fujian, Guangdong, and Hakka provenance are also eaten throughout the province, reflecting the origins of other migrant Hainanese.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, large numbers of Hainanese migrated to Southeast Asia for business and trade, spreading delicacies such as Wenchang chicken to new regions. Many later returned to the island with new recipes and ingredients from abroad. In the 1950s and 60s, thousands of huaqiao returned to Hainan at the invitation of China’s government, and settled on farms where they cultivated another exotic import: coffee. Today, Hainan, via the counties of Fushan and Xinglong, claims to be the only Chinese province with a coffee-drinking culture, and wants to promote its local brews around the world.

Nature’s Charm

“This recipe uses no sauce, but only natural flavors,” Su rhapsodized of his vegetable stew. “It flows with cream and liquid. The soup is like a light breeze, and the grits and beans are put in harmoniously.”

Natural ingredients and subtle flavors continue to define Hainanese or Qiong (琼) cuisine today—characteristics which may, at first, be seen as alien to mainland diners accustomed to the tastes of numbing Sichuan spices, rich Shandong sauces, or sweet Jiangnan glazes. Boiling raw ingredients in clear soup is one of the most popular cooking methods on the island. Seasonings are often mixed into the dish by the chef after cooking, or even by the diner after it is served, so that each element in the dish retains its essential flavors and textures with subtle modifications to suit each palate.

Another major quirk of Qiong cuisine is its naming. Whereas other well-known regional fare—kung pao chicken, Dongpo pork—are individual entrees with exact ingredients, seasonings, and methods of preparation, Hainanese dishes such as Wenchang chicken and Dongshan goat have no set recipe. Instead, they are named after their chief raw ingredient, and tend to give instructions for how to raise an animal or grow a plant, rather than how to cook it.

Don’t be surprised if you order one of the “Four Famous Dishes” of the island, and the waiter waits patiently for you to describe how you want it prepared. Get creative!

Hot Stuff

Hainan’s cuisine may have a reputation for subtlety, but don’t mistake “natural” for “bland”: It’s also one of the Chinese provinces better known for being able to handle spicy food, thanks to a favorite local seasoning known as “yellow lantern chili pepper” (黄灯笼辣椒).

Widely cultivated in the eastern part of the province, the lantern pepper is a native Hainan variety of the chili known as Capsicum chinense, a Latin American import believed to have arrived on the island 500 years ago due to maritime trade. The pepper was a special favorite of the Miao people. Living in highland areas deprived of access to fresh meat and the government-controlled salt trade, the Miao traditionally pickled and preserve their food with spices. Some recipes, such as the Miao-influenced Lingshui sour noodles, call specifically for the pepper to be added. Most restaurants in Hainan, though, will provide a jar of a lantern pepper sauce on each table, which patrons can add to Wenchang chicken, rice noodles, and other dishes according to their own taste.

Lantern pepper hot sauce is also a standard offering on flights with the province’s flagship Hainan Airlines, and a popular souvenir for tourists to take home. Its tawny color and fruity aroma can trick diners into underestimating its potency, but make no mistake—the result is a slow then suddenly forceful burn with a tart aftertaste, if you can still feel your tongue by that point.

Cover image from InterPhoto

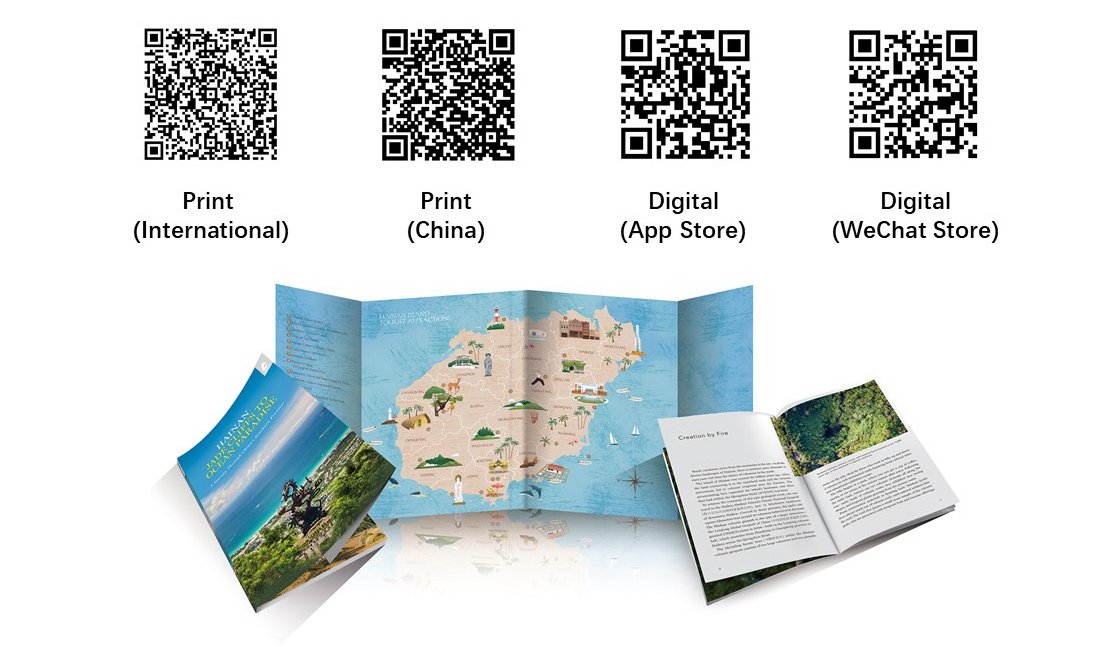

Excerpt taken from Hainan: Jade Cliffs to Ocean Paradise, TWOC’s new guide to China’s southernmost province. Get your copy today from our WeChat store!