A now-deleted Twitter account offered humorous historical lessons on the Ming dynasty’s last emperor

A doomed leader sits alone, awaiting the inevitable. His time in power is almost over. He feels betrayed by his own people, by the sycophants who downplayed crises by telling him only what he wanted to hear, and by the naysayers whose only answer in an emergency was to blame the leader for failing to lead.

It’s a good thing this despondent ruler didn’t have access to Twitter. Or did he?

Though he died nearly 400 years ago in Beijing, the Chongzhen Emperor of the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) recently found brief new life as a social media star. A now-deleted Twitter account, which takes the identity of the last Ming emperor, kept busy parodying the last days of Donald Trump’s presidency in the US. Staying in character throughout his tweets, account’s unknown owner satirized the recent Trump administration while offering humorous takes on a historical emperor whose reign was tumultuous, but never boring.

Born Zhu Youjian (朱由检) on February 6, 1611, the Chongzhen Emperor was the fifth son of his father, the Taichang Emperor, and was the spare to the throne after his elder brother, the Tianqi Emperor. In 1627, the 17-year-old Zhu Youjian came to power unexpectedly in an empire in crisis. The country faced grave threats from two fronts: The Manchus to the north, and rebellious peasants squeezed by economic pressures in the west.

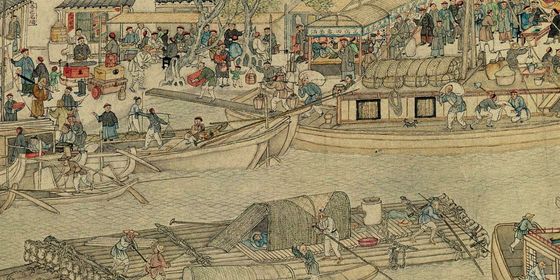

In the 17th century, the Little Ice Age altered weather patterns and shortened the growing season across the northern hemisphere. Decades of corruption, fiscal mismanagement, and poor adminsitrationhad also left the Ming coffers empty. Angry and disaffected farmers eagerly listened to the opportunistic insurgents, who filled their minds with delusions of grandeur while nurturing their own ruthless ambitions.

In 1627, the Chongzhen Emperor was young. He was energetic. He was known to be a hard worker. More importantly, he wasn’t his father (who pooped himself to death after just 28 days in power) or his brother (who let his old wet nurse and the eunuch Wei Zhongxian run the empire into the ground while he devoted his time to hammering wood; yes, that is a double entendre.)

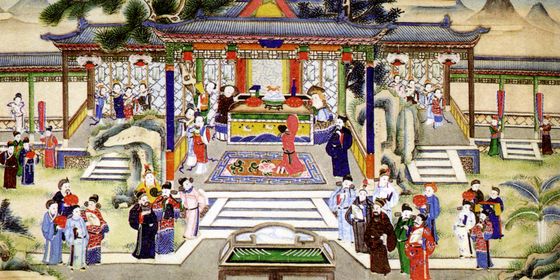

Despite all of the problems facing the Ming, the ascension of the Chongzhen Emperor was seen by many as the beginning of a new era. It was time to Make the Ming Great Again. He had supporters among the official class, including a group of literati from the south known as the Restoration Society, who were itching to drain the eunuch swamp.

These intellectuals loved that their new emperor, unlike his idiot brother, actually liked to read. The Chongzhen Emperor revived the Lessons of Classics Mat, and invited scholars to the palace to lecture him on history, philosophy, and their application to current events.

The emperor was a good student. But he was also inexperienced, and prone to dithering and procrastinating, only to act rashly when decisions needed to be made. Worst of all, he was a terrible judge of character and an HR manager’s nightmare.

The emperor employed in his court all who offered a little flattery, some positive energy, and the promise of a quick fix for whatever problem was vexing the emperor that day. But the crises facing the country were stubbornly resistant to simple solutions. Repeated failures made the emperor susceptible to political rumors and conspiracy theories. He became a master of magical thinking, bending reality to avoid an inconvenient truth: He was a terrible leader in an era that required great leadership.

The result was toxic factionalism, savage infighting, and blindingly rapid turnover in critical positions at court. Of the approximately 160 men who were appointed to top cabinet positions in the 276-year history of the Ming dynasty, 50 held the post during the Chongzhen Emperor’s reign. Lucky officials only got fired when the emperor tired of their solutions: During his 17 years on the throne, the Chongzhen Emperor ordered the execution of seven military governors, 11 regional commanders, and 14 heads of the Board of War.

In the 1630s, rebel armies led by peasants Li Zicheng (李自成) and Zhang Xianzhong (张献忠) swept out of the northwest and into central China. To deal with the threat, the court turned to a renowned military commander, Hong Chengchou (洪承畴). A careful planner and brilliant strategist, Hong turned back the marauders and nearly wiped out Li’s entire army in 1638.

The emperor was impressed, so just as Hong was preparing to deal a fatal blow to the rebels, the emperor ordered him to march his entire army several hundred miles to northeastern China to defend the Great Wall against the empire’s other existential threat: the Manchus.

Putting the “Great” back in “Great Ming”

Arriving at the Great Wall, Hong wanted to take time to develop a strategy. But the emperor couldn’t wait, and Hong was ordered to advance only to get trounced by the Manchus.

Word got back to Beijing that Hong had been taken prisoner and executed. In fact, he had defected to his Manchu captors. One sign you may have lost your employees’ loyalty is when they start applying for jobs with your enemies—even if their new employers make them get funny haircuts and once tried to kill them on the battlefield.

By 1644, all the problems of the Chongzhen Emperor’s reign had come together in the worst possible way. By transferring Hong just as he was making gains in the northwest, the emperor allowed the armies of Li and Zhang to regroup and continue their advance eastward. The defection of Hong left the defense of the Wall in the young and unsteady hands of a general named Wu Sangui, who was spending an inordinate amount of time with his new girlfriend. The emperor was caught in the middle, like minced pork about to be rolled and steamed in a very violent and angry jiaozi.

In early 1644, the emperor called together what was left of his court. His ministers’ suggestions for saving the empire were mostly unhelpful, ranging from printing paper money—which hadn’t worked even when the dynasty was fiscally sound—to moving the capital to Nanjing, thus recalling when the Song dynasty lost half of the country to another group of overly eager northern invaders in the 12th century.

The emperor flew into a rage. Those ministers who could, resigned, quietly packed up their families and homes, and fled the doomed capital as far and as fast as their servants could carry them.

The armies of Li and Zhang entered the capital in April of 1644. Li had already named himself the ruler of a new dynasty, Shun, and was just waiting for check-in time at the Forbidden City. The southern part of Beijing was already on fire, and the emperor knew he was doomed.

On April 25, 1644, the Chongzhen Emperor got drunk, dressed in his finest robes, forced his empress to commit suicide (he never liked her anyway), smuggled his sons to safety, and then gathered his remaining concubines and daughters together in the palace and dismembered them with a sword (to stop them from being dishonored by the rebels, allegedly).

He then stumbled out the back door of the Forbidden City, climbed up the hill behind his palace, and hanged himself. He was 33 years old. According to legend, a favored eunuch, Wang Cheng’en (王承恩), followed the emperor and cut the body down. It would be three more days before the soldiers of Li Zicheng discovered the corpse.

The Chongzhen Emperor started his rule with great ambition, but little vision or leadership skills. The result was a disastrous reign that checked all the boxes for “last emperor of a dying dynasty.” Historians dismiss him. Popular culture mocks him. But hey…what does that matter if you were once (and future?) Twitter star?

Cover image of stone tablet marking the spot where the Chongzhen Emperor hanged himself, in today’s Jingshan Park in Beijing, from VCG