Changing centuries-old dining norms to fight the spread of Covid-19

“Divide food, not love” runs a slogan on a billboard in central Shanghai, while on the Beijing subway a screen shows a cartoon pair of chopsticks dancing to the “Song of the Communal Chopstick.”

These metropolises, like many other cities across China, have launched a “tongue-tip hygiene” campaign to encourage a “dinner table revolution” in response to Covid-19.

The campaign aims to change aspects of China’s dining culture and etiquette, some of it centuries old, that might contribute to the spread of infectious diseases. At Chinese meals, communal dishes of food are generally placed on the table and shared by all, with diners using their chopsticks to pick out food for themselves and others; often the same chopsticks one uses to eat.

Now, public notices and new regulations encourage diners to use “communal serving” chopsticks and spoons (公筷公勺) for dishing out the food, and a separate personal pair for eating. Diners are also encouraged to practice “separate meals (分餐),” where they each receive their own serving (as is common in Western restaurants) rather than order dishes to share.

Since the coronavirus first emerged in Wuhan, a number of infection clusters have been linked to group meals. On January 18, a mass meal of over 40,000 people organized by a Wuhan residential community was widely condemned, while a family dinner in Nanjing reportedly led to nine infected; a group of friends dining together in Nanchang resulted in 52 people being placed in quarantine.

Many Chinese foods are traditionally served communally

At the beginning of March, the city of Taizhou announced the “Rules on Communal Spoon and Communal Chopsticks,” mandating that restaurants provide separate serving spoons and chopsticks, and specifying the length, color and labeling for such utensils to minimize confusion (serving chopsticks should be 3–4 cm longer than personal chopsticks, and should be white or red). On March 17, 100 restaurants in Shanghai committed to a city government initiative to provide separate serving utensils with every dish.

The changes are considered necessary to fight the spread of Covid-19 and other infectious diseases. On March 20, Beijing municipal propaganda department deputy minister Teng Shengping argued at a press conference that “using contaminated chopsticks is one of the main channels for infection by pathogens.”A recent experiment by the Hangzhou Center for Disease Control found that using communal serving chopsticks could reduce bacteria found in shared dishes by up to 250 times.

However, eating habits and cultural norms around dining etiquette are likely to prove formidable barriers to changing centuries-old traditions. It’s not clear exactly when communal eating became commonplace, but the sharing of food has come to be a symbol of respect and affection between diners.

The Global Times dates the practice of communal eating to the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), when teahouses, pubs, and entertainment venues began to proliferate in the cities. The dancing serving chopstick in the Beijing subway cartoon dates itself to 1127.

Separate portions seem to have been common before this period, at least among the upper classes, who could afford more cutlery and utensils. A re-telling of the Banquet at Hongmen in the Records of the Grand Historian in 206 BCE, featuring prominent rebels Liu Bang and Xiang Yu, describes guests enjoying separate meals behind their own tables. Similarly, in 10th-century artist Gu Hongzhong’s Night Revels of Han Xizai, nobles are shown each with a separate portion of food at their own table.

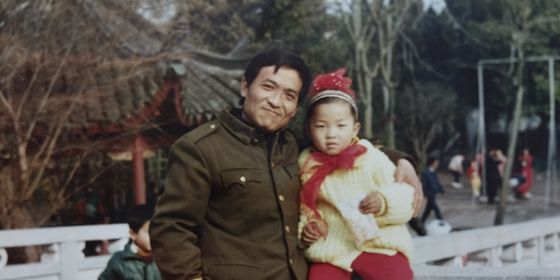

Serving others with one’s own chopsticks is considered a sign of affection

Since then, however, eating communally slowly became the norm, and centuries of habit may prove difficult to break. “My mother would slap me if I refused food from her,” Liu Jingzhu, a 30-year-old from Liaoning province, tells TWOC, describing a practice where diners would pick up food with their own chopstick and place it in the bowl of guests or children, usually as a sign of respect or affection. “I think if you know the person, if they’re family or friends, it’s still okay to share.”

According to the Beijing Daily, a resident surnamed Ma has implemented a system of “separate meals” and communal serving chopsticks in her home since 2017, but even she hesitates when guests come over. “If it’s a very close friend or relative I just say directly, ‘for health considerations, everyone must use common chopsticks and common spoons,'” Ma told journalists. But often guests are put off: “Do you think we’re dirty?” is a common reply.

The push to change dining habits is not new. During and after the 1910 plague epidemic in northeastern China, Malaysian-Chinese epidemiologist Wu Lien-teh promoted avoidance of communal eating to reduce the risk of cross-infection, and encouraged the use of the “lazy Susan” turntable. In 1984, Hu Yaobang, then general secretary of the Communist Party, suggested that citizens “eat Chinese food the Western way—that is, each from his own plate.”

During the 2003 SARS epidemic, too, the Chinese government encouraged similar measures. In an academic paper in 2004, staff at the Epidemic Prevention and Control Center in Jilin province wrote: “The SARS outbreak made the significance of separate meals evident to us again. As public awareness of disease prevention continues to be raised, the separate meal system is sure to be accepted by the public.”

But as the SARS disease waned, so did the push for more hygienic eating habits. Even now, the campaign encouraging restaurants to provide communal serving chopsticks and spoons, limit restaurant capacity, ensure social distancing, and seat a maximum of three diners per table has seen patchy implementation.

Of eight restaurants in Beijing TWOC visited over two weeks in May, only one provided communal chopsticks unprompted and enforced social distancing rules inside. Likewise, an online poll of 210,000 respondents by Jiangsu News in March found that 30 percent thought it was too inconvenient to use communal serving chopsticks when dining out, compared with 27 percent who said they already use them.

In an article supporting the use of communal serving utensils, the Guangming Daily outlined the emotional barriers to encouraging their uptake: “Chinese people’s dining tables bear the weight of a lot of emotion, the older generation’s love and care for younger generations is often embodied by placing piece after piece of meat on their plate, or picking bits of food up and placing them directly in the child’s mouth.” But, it urged its readers, “a civilized dinner table reflects a civilized society.”

All images from VCG