Mixed-race Chinese struggle with identity and acceptance—especially if they have dark skin

“I’m at a stage now where I don’t want to go back to the USA, but neither do I have the patience to carry on living in China,” explains Jesse Bowens, a 25-year old Chinese-African-American student living in Beijing, only weeks before her wedding to 45-year old Xu Haifeng last November.

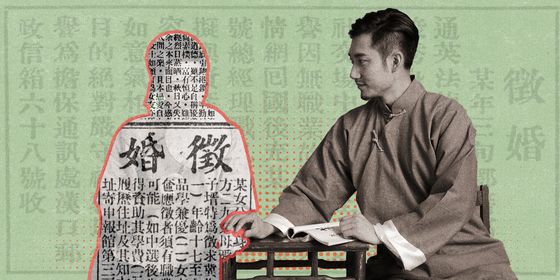

Known in China as hunxueer (混血儿), or literally “mixed blood children,” mixed-race Chinese experience a gamut of emotions when living in China. According to the South China Morning Post, parents of hunxueer who have been sent to the privileged international school system have displayed concern at their children’s lack of interest, and even rejection, of Chinese culture and language. (Other young mixed-race Chinese have told TWOC about the advantages of being bilingual and “understanding” both cultures, which often simply means feeling more affinity towards locals than other children)

But Bowens, the great-granddaughter of a Kuomintang lieutenant who died fighting the Japanese, found herself drawn to Chinese culture from a young age. Growing up in San Francisco’s Bay Area, she learned her first characters from Panda Express paraphernalia: namely, “water” (水) on drinking cups at the Chinese-American fast food outlet. As a university student at Berkeley, Bowens took Chinese classes, and she fell in love with a Chinese man after coming to Beijing for her Master’s degree.

Bowens and Xu met at church in Beijing

Being dark-skinned, Bowens sometimes echoes the accounts of racial discrimination by African or African-Americans in China; at other times, she feels her experiences are more complex.

During a trip to her ancestral town in Jiangsu province last summer, she noted her embarrassment when asserting her Chinese identity to confused locals, but beamed when remembering a day when she was treated like a Beijinger when skating on the frozen lake at the Summer Palace.

On TV and the internet, though, there is a clear hierarchy in the way white and dark-skinned hunxueer are portrayed. Chinese films and brands often bank on the large number of famous actresses and models from mixed Caucasian and Chinese backgrounds, such as Celina Jade, to add international appeal.

Some netizens regard these hunxueer as being a perfect fusion of East and West, and thus more appealing than their fully Chinese counterparts in the entertainment industry:

“…[Wolf Warrior 2‘s] Lu Jingwei…[and Detective Chinatown‘s] Liu Chengyu…have a few things in common: both are hunxueer, have martial arts skills, and have advanced degrees. In rejecting the wanghong and ‘plastic surgery’ look of the entertainment industry, a hunxueer’s visage stands out for its cleanliness, clear-cut features, possessing the graceful beauty of Eastern women and the exotic look of Western women” (Weibo)

A comment to the above post: “Asian face and European body, what’s there not to like?”

“Lu Jing Shan reveals that she was once mocked for being hunxueer. If you had those looks, would you be afraid of mockery?” (Weibo)

“It must have been foreigners who mocked her, Chinese people wouldn’t do such a thing—I personally feel that hunxueer usually fit into Chinese beauty standards”

On the other hand, when Shanghai student Lou Jing appeared on Dragon TV’s talent show “Go Oriental Angel” in 2009, as one of five finalists from her home city, she was met with a barrage of racist slander from netizens; the fact that Lou Jing described herself as Shanghainese and spoke the dialect perfectly did little to help her case. After it was made public that Lou Jing was born from her Chinese mother’s affair with an African-American man (who left before she was born), adultery and illegitimacy were added to her family’s supposed sins.

Bowens says she has also been in situations where her dark skin appeared to be “worth” less.

A recent video project that featured her, Xu, and other foreign-Chinese couples in China gave Bowens and Xu much less screen time than the other couples—who were all Caucasian-Chinese—though they were the only married couple. After the video aired, recalls Bowens, “The other couples all had an online following, which is a by-product of being white.”

For dark-skinned hunxueer born or residing in China, “proving” themselves Chinese, rather than assert their mixed-race ancestry, still seems to be the main goal.

Since 2009, Ding Hui, the first Chinese volleyball player of African ancestry to get recruited to the national team, has repeated in interviews, “I’m not a foreigner; I’m Chinese.” In 2017, netizens rushed to welcome the addition of 14-year-old Wang Mu, a Tanzanian-Chinese hunxueer from Wenzhou, to China’s U14 national youth squad, hailing him as the future of Chinese football. Yet implicit behind this praise was the centuries-old stereotype that people of African descent are physically gifted, and primarily good at sports.

When national pride is on the line, fear about racial purity take a backstage; after Japan won the silver medal in the 4x100m relay at the 2016 Olympics, breaking the Asian record previously held by China, Chinese netizens drew positive attention to the dark-skinned member of the Japanese relay team, Japanese-Jamaican Asuka Cambridge, and called on Chinese teams to add more hunxueer.

From the cases of athletically gifted first-generation mixed African-Chinese, it seems that mixing genetics is acceptable—if it serves the Chinese nation. Many netizens have already started describing Chinese-African hunxueer as China’s “57th ethnicity,” a marked contrast with the way many described African expat communities in Guangzhou as an “invasion” just a few years ago.

Bowens has noted the dark sides to a form of cultural “acceptance” that glosses over—rather than celebrates—differences. “Chinese people may find it strange that me and Haifeng are together,” she says, “but once he tells them I’m Chinese, they’re like ‘oh, that makes sense,’ or, ‘totally fine, you’re one of us.’” She also has trouble identifying as Chinese due to her mixed heritage: She cannot stand bureaucratic procedures in China or certain sexist attitudes from her Chinese peers, and, having been raised under year-round Californian sunshine, she found Beijing’s polluted air particularly hard to endure. Bowens now works abroad, while her husband remains in Beijing.

As for the majority of China’s dark-skinned hunxueer who are not sporting prodigies, or who don’t have the language skills or social networks to migrate overseas, integration and equal opportunities are not yet on the horizon. Lou Jing has disappeared from social media, and one wonders whether she has still been able to live a normal life in Chinese society after her short-lived infamy. Ding Hui, by contrast, simply seeks acceptance from Chinese compatriots, rather than becoming a celebrity off the back of his exotic genes.

“I hope Chinese people will stop being curious about me,” Ding said in an interview, after qualifying in the 2009 National Volleyball Team tryouts. “There is no need to care so much about my appearance.”