National Museum exhibition marks the October Revolution with nice art…and little else

An elderly woman has her nose almost pressed to the glass as she mutters words printed in Cyrillic on a poster filled with hammer-and-sickle motifs. “Congratulations to Comrade Lenin…” she translates to herself in Chinese. She’s the only visitor bothering to do so.

In May, historian and fantasy-fiction writer China Miéville visited Russia to explore the memory of the “October Revolution”—the 1917 Bolshevik uprising that gave the world its first communist state. “They will say there was a struggle,” one Russian told him, “and that eventually, Russia won.” If the revolution’s centennial exhibition at the National Museum of China is any indication, these thoughts are just as applicable to China.

Opening on November 7, the revolution’s exact centennial (October 25 by the calendar used in Russia at the time), the “Exhibition in Memory of the 100th Anniversary of the October Revolution” is co-hosted by the State Historical Museum of Russia and runs until February 7. Divided into three sections—The Great Revolution, The People’s Memory, and Sino-Soviet Friendship—contained in a single exhibition hall, the compact collection includes artwork, posters, Soviet leaders’ personal affects, and gifts from China, presented with sparse explanation of each item’s historical meaning and no attempt at an overarching narrative. It’s best described as a selection of curios and memorabilia related to the title event—a commemoration, that is, of how the revolution has been commemorated in the past.

This reticence is unsurprising, considering the mixed feelings about the revolution and its legacy back in Russia, to say nothing of the intrinsic politics involved in trying to narrate the past in China. The centennial saw no official celebration in China, but red pilgrims have still been flocking to Russia to tour symbolic sites of the revolution—according to Russia’s Federal Agency for Tourism (paywall), the number of China tourists increased by 36 percent in the first half of this year. In his closing report to the Chinese Communist Party’s 19th Party Congress, delivered shortly before November 7, General-Secretary Xi Jinping acknowledged, “One hundred years ago, the salvoes of the October Revolution brought Marxist-Leninism to China”—the same phrase that has been repeated in countless official speeches and credited to CPC forebears like Lin Biao, Mao Zedong, and even Party co-founder Li Dazhao.

Xi continued, “From that moment on, the Chinese people have had the Party as a backbone…and the mindset of the Chinese people has changed, from passivity to taking the initiative.” The revolution is symbolic, not historical: China was motivated to struggle and “win” what it has today, regardless of the details in between. In the exhibition, China’s own memories are barely present; the Sino-Soviet section is the smallest of the collection. Apart from the placards that repeat congratulatory messages from historical figures after the revolution—Sun Yat-sen, for one, telegraphed Lenin expressing a “wish for China and Russia to unite to struggle together—Chinese leaders are afforded little part on the Soviet stage. The exception is perhaps one propaganda poster, where Stalin shakes hands with Mao Zedong, the latter looking oddly subdued for those used to seeing him as the focal point of Communist imagery.

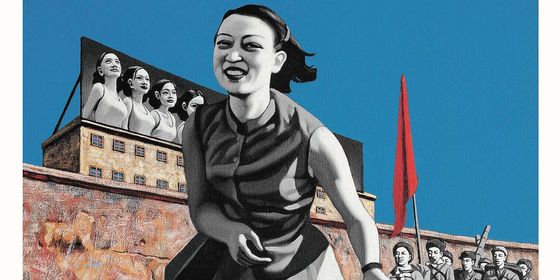

If nothing else, the exhibition is at least an excellent summary in the evolution of Soviet art styles through the ages. The artworks focus almost exclusively on depictions of the October Revolution and propaganda posters commemorating past anniversaries from year to year. Moving from section to section, it’s possible to follow the transition from vivid oil paintings and bold geometric designs of the 1920s to the classical proportions of the Stalin era, and again to the bright colors and scientific motifs of the 80s. “It’s like the start of a movie,” a young visitor remarks, standing in front of a 1947 poster for the revolution’s 30th anniversary, where beams of light crisscross beneath a gold-tinted tower; he’s comparing it to the logo of 20th Century Fox. “I didn’t know they also had these styles.” It’s a good place to get context and exposure to a part of art history that doesn’t always get a fair shake from mainstream critics.

Revolutionaries storming the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg (National Museum)

The old woman I saw reading the posters shares her own memories as we leave. “I learned Russian in middle and high school, then became a Russian teacher. In school we learned about how Stalin took power [after] Lenin, I still remember all the details perfectly clearly.” These memories, now shared by a dwindling generation, don’t seem to be the kind that China wants to replenish in the New Era.

All other photos by Hatty Liu