Even Chinese parents find matchmaking corners embarrassing, though a “necessary evil”

“Lots of media have been coming here,” says Mr. Zhu, a father in his 60s who regularly attends Beijing’s Zhongshan Park matchmaking corner with his 30-year-old daughter. “Around 2 or 3 p.m. is usually when the crowds come,” his daughter, Ms. Zhu, adds. It is 1:30 p.m. when TWOC visits, yet there is already a line jostling to look at prospective dates.

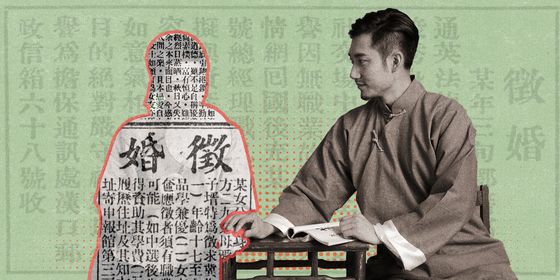

The ancient art of xiangqin (相亲, matchmaking) is back in the news, following reports last week on the growing materialism, superstition, and parental entitlement on display at China’s infamous public “marriage markets” (相亲角, literally “matchmaking corner”). After Phoenix Weekly and the Beijing Evening News profiled the markets, last Wednesday, Chinese media pounced on the opportunity to criticize the traditional views of marriage in modern China.

The surge in interest has irritated regulars. “Don’t take any pictures; especially don’t take any pictures of the names [and CVs] on the ground,” a woman surnamed Meng warned us as she passed. “Do it, and the old ladies will surround you–they’ll run you off. They’re afraid of people selling that information.” But Ms. Zhu believes that some are simply embarrassed about being seen. “Young people do come, but they come with the market’s about to close, at 5 p.m. or 6 p.m.; they’re a little self-conscious.”

***

Situated in the northernmost section of the park, up against the 600-year-old moat encircling the Forbidden City, the Zhongshan marriage market feels like an open secret. Scores of people sit guardedly at the curb, beside hand-written CVs advertising their (or their absent children’s) age, income, family assets, and education and employment history in a puzzling intersection of prudence and imprudence.

Make eye contact, and they’ll stand with an expectant smile—“Are you looking?”—before sinking back into indifference at discovering their new friend is only browsing, doesn’t meet any number of deal-breakers such as age, job type, or household registration status (hukou), or—perhaps least welcome of all—is only a reporter.

Mr. Zhu and his daughter are among the few attendees willing to talk openly about the matchmaking corner. “I don’t have anything to hide,” Mr. Zhu tells TWOC

Mr. Li, a 44-year-old entrepreneur from Hunan, is friendly when TWOC approaches, perhaps because he has other concerns on his mind. “Most people here are scamming,” he claims. His cynicism may be due to the fact he has been coming to the matchmaking corner for eight years with no success. “You don’t come here to look for people; you’re looking for money.”

Mr. Li says his efforts to use online dating and matchmaking through WeChat group chats were stonewalled. “Online, you just get dates, they’ll eat and drink with you and wave goodbye. On WeChat, just like here, they’re just showing off: How much you make, how many houses you own. I have two apartments, but they hear it’s in Shunyi [a Beijing suburb], and say, ‘We won’t consider you.’ Your apartment has to be within the Second or Third Ring Road.”

Li has a deal-breaker of his own—“Just Beijing hukou, everything else is negotiable. It makes it easier for the kids to go to school in the future.” Many other attendees observe a caste system based on hukou location. “Beijingers don’t look for them, so it’s outsiders who look for [other] outsiders,” explains Ms. Meng, who spoke with a non-Beijing accent.

Under China’s current hukou system—a relic of the planned economy that remains largely unreformed—household registration determines where newlyweds can purchase homes, educate offspring, and even affects prospects as remote as whether their putative children can get into top universities.

Economic considerations, however, are paramount. According to their CVs, everyone at Zhongshan Park attended a major university, earns a high four or five-figure salary, has a house in their family name, and an important job at (in order of desirability) a state-owned organization, Fortune 500 corporation, or rising start-up in Zhongguancun. But even for families that check all the boxes, Zhongshan Park is no easy place to find a mate.

Neither Ms. Zhu nor her father know anyone who has successfully made a match—though they’ve heard plenty of talk—but visit anyway because of the increasing “estrangement” of the big city. “See, Beijing—you live on the east side, I live on the west side, it’s basically a long-distance relationship,” Mr. Zhu quips. “With cross-province relationships, there’s high-speed rail. But Beijing? Traffic jams!”

“You don’t know your neighbors, they don’t come and say hello anymore. You don’t know what they do [for a living],” he adds, growing more serious. “It’s not putting pressure on my daughter, but giving her an opportunity—all of her colleagues are female, how else is she supposed to meet someone?” (Ms. Zhu says she has a bachelor’s degree and works as a teacher).

It’s a reversal of a past still etched in the memory of many: Formerly China’s biggest hub of state-operated working units (danwei), Beijing is one of many cities grappling with the breakdown of state-prescribed social relations as a result of urbanization and privatization. Finding a partner through conventional means is more difficult. Li came here almost 30 years ago, when his father worked at Capital Steel, Beijing’s biggest SOE; these days, all he has is his status as a self-made businessman, and it’s not quite getting him the acceptance that he wants.

“If my parents left me a fortune, I would have not struggled on my own all those years…I started with nothing, now I have my own company and house,” he said. “It spared me little time and energy to get married when I was younger.” And so he returns to the matchmaking corner year after year, leaning defiantly against a tree near the end of the path, airing his views to passers-by.

***

Unlike many, Ms. Dong didn’t wander away after learning we aren’t here to make a match. She wants to talk to young people because her daughter doesn’t approve of what she’s doing. “I’m here behind my daughter’s back,” she admits. “I saw a report about this place on TV this past week, and I wanted to see what it was about.”

Like Mr. Zhu, she’s anxious about her daughter’s prospects because of the challenges of modern life. “In today’s society, cities are getting bigger and bigger, and farther apart. Everybody’s so busy and has so much pressure,” she said. “My daughter was an excellent student, with a Master’s from Renmin University; she has to work so hard at her job, working overtime, there’s really no time to look…I wanted to lessen one burden for her.”

What she has seen, though, has made her “draw a question mark over the whole process,” she says. Can you really find someone here? There’s already a generation gap between parents and kids–parents come here and meet other parents, but will the kids get along?

“There is no discussion of feelings,” she tells TWOC. “You find out how their families are situated, but you don’t know what kind of person they are. You don’t even know what they look like; there’s no picture most of the time.”

“Life is just about finding a good enough person to passing the days with—eat, sleep, go to work—not like the matchmaking corner, where it’s all about competition,” says Mr. Li, an eight-year veteran of the Zhongshan Park marriage market

What Ms. Dong regrets is not encouraging her daughter to settle down with while she was studying. “She was a straight-A student, so she focused on her studies,” she repeats. “Now she enjoys the single life, busying in her work, and hobbies such as traveling—she traveled to Europe, booking air tickets all on her own—but everyone else is busy with their own lives too.”

“You see men here over 40, or even 50, looking for young, beautiful partners in their 20-30,” says Li.“On the contrary, it’s difficult for women over 30 to find a partner, since people think their best time for childbirth is past.”

Ms. Dong’s preferred solution harkens to the days of the planned economy—“I think if the government really wanted to solve this problem, they should have different danwei organize events for single people. That way you’ll really meet someone with similar interests and background.” Until then, she tells TWOC self-deprecatingly, fussy mothers and matchmaking corners are necessary evils.

“You would think that, at 18, your children will move out and be independent, but it’s so exhausting to be a parent today. Now, when she was at school—it was like a big supermarket, plenty to choose from and plenty of time,” she says, growing more introspective. “And what’s more, people were more innocent there: They don’t have all these ulterior motives and demands when getting to know you.”

Tan Yunfei and Hatty Liu contributed to this report

Cover image of matchmaking corner in Sichuan from blog.sina.com. Additional photos by Hatty Liu

Market Values is a story from our issue, “Disaster Warning.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.