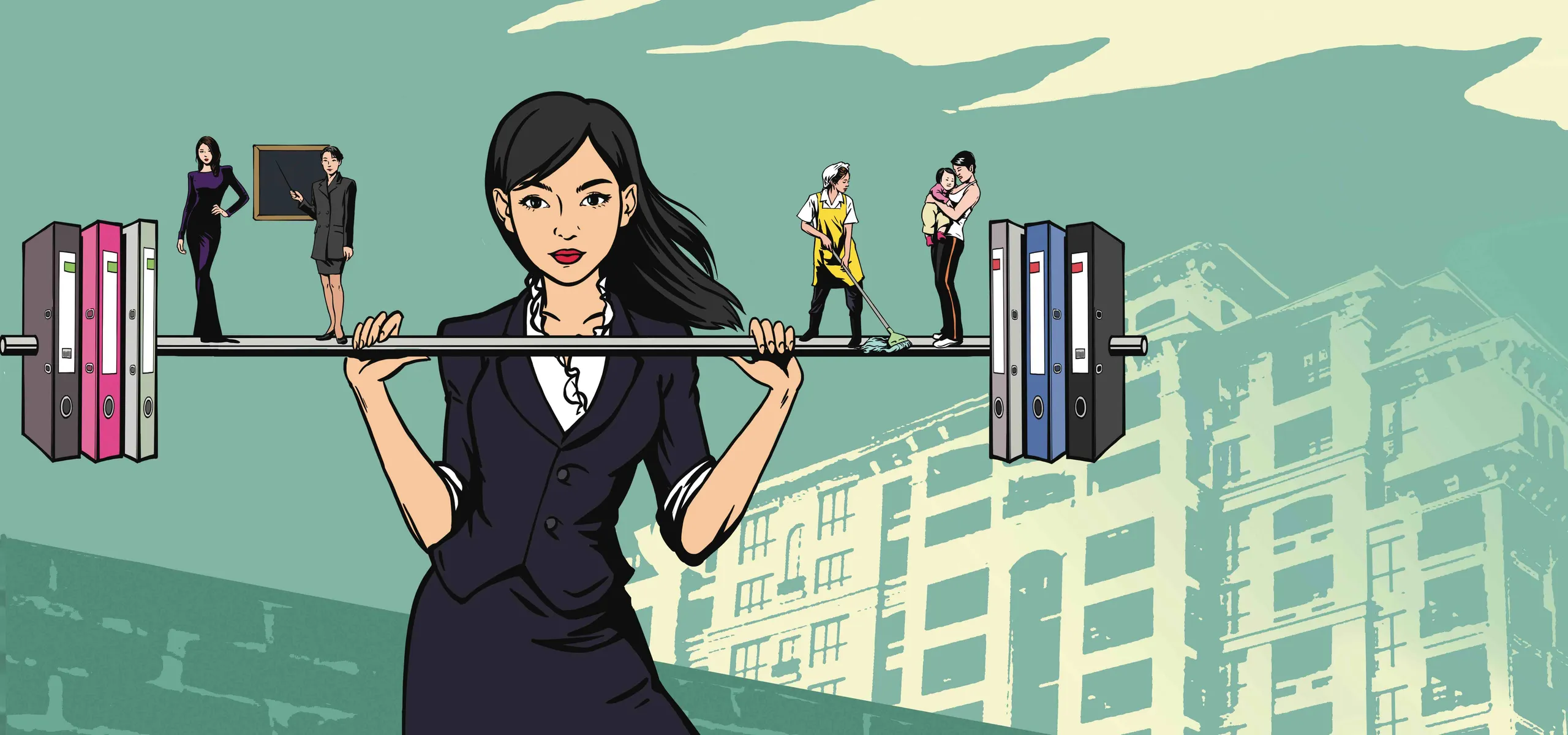

What the women of China earn, what they deserve, and what they’re missing

Guidelines, laws, statutes, policy statements—the structure for female equality in the workplace is there. But is it working? China suffers many of the same ethical and practical tribulations of gender equality in the office as elsewhere in the world, but the Chinese workplace is a very special monster. As China builds for a century of success, the concept of equal pay for equal work for women seems to take a back seat, and trumping traditional gender roles can be difficult, especially in a newly-urbanized economy that hasn’t quite settled. And, of course, beyond the question of discrimination is one of harassment; changing laws mean nothing when minds remain stubbornly stagnant. The 21st century economy has been defined by the “Chinese miracle”, and the women who shaped it want what’s due.

INVOICE: 1/2 SKY

If you’re a woman in China, statistically, you earn about two-thirds of the pay your male peers get—that is, if you live in a city. In the countryside that proportion drops to just over half. Those figures come from a survey by the All China Women’s Federation, though one has to wonder about figures from an organization which has been pilloried by some academics for perpetuating the “leftover woman” trope (that any woman in her late 20s is reaching a marriage use-by date).

All of this illustrates the point that at both an institutional and individual level China remains very much a man’s world—and this is very apparent in workplaces. However, the ways in which gender issues affect salaries can be complicated.

First and foremost, when calculating salary differences, it is important to consider the jobs themselves. While a company may point to the fact its female workforce receives a salary calculated by the same standards as the male employees, it may overlook the number of women in well-paid roles. The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap report in 2015 found that only 18 percent of Chinese companies have women in top management roles.

There are, of course, industries in which women are well represented. A 2015 International Labor Organization (ILO) report focused on the Asia Pacific found that in China women had come to dominate four service sectors: hotels and catering, financial intermediation, education, and health and social welfare.

But are these really the areas women should feel lucky to dominate?

“The analysis of average earnings by occupation and sector suggests a stronger likelihood on the existence of a gender pay gap,” the report notes. “In hotels and catering services and the health, social securities, and social welfare sectors—two of the four female-dominated sectors in 2012—the average (annual) earnings for business service personnel lay below average at 29,500 RMB and 37,600 RMB in 2013.” For reference, the national average was 45,100 RMB.

No doubt, things are in many ways better than they were in the past. China’s urbanization process is an economic boon to most. But it would seem the benefits of this societal transition haven’t been spread evenly. The ILO report noted that “while the move out of agricultural work may have resulted in some improvements in the earnings of women and men, women tend to dominate in the lowest-paying occupations.”

As Lü Pin, a feminist media commentator and activist points out, these kinds of gender discrepancies are difficult because they go beyond any easily identifiable root causes. “For those of us trying to make change, I don’t think pinning down the cause is the most important thing. We’re concerned with how to stop these [inequalities] from happening.”

“With regard to the pay disparity, it’s definitely linked to basic gender-based discrimination, but institutions can make rules to prevent discrimination, that goes without question. In other countries they also have such rules, and they have to consider many factors,” Lü says.

Despite the fact that China’s constitution specifically prohibits gender discrimination in hiring, the nuts and bolts of this policy prove difficult to implement and often result in misguided policies designed to “protect” women which instead exclude them.

The extent to which discrimination is responsible for the persistent gender pay gap is contentious. Many scholars agree discrimination plays a role, but it is incredibly difficult to make any concrete assertions from the available data. Some reports say it is the overwhelming cause, others downplay its significance.

Worryingly, there are reasons to think the situation might be getting worse.

The ILO report states that despite some legislative achievements, “in recent years, there appears to be a re-emergence of gender stereotypes related to women’s and men’s roles in early capitalist or market economy societies, i.e. men as breadwinners and women as caregivers.”

This is supported by plenty of casual observations. Simply by opening a newspaper or pulling up an employment-wanted section of a website, anyone can come across a wide array of advertisements for jobs that specifically request men or women for positions that ought to have no gender requirement. For years the proportion of advertisements specifying male applicants had been on the decrease, but in 2010 that trend bottomed out and it started to rise once again. The ILO report notes that it’s particularly pronounced for new graduates and corresponds with a tougher job market, which most economists are predicting for China over the coming few years.

For quite some time, there have been reasons to cast doubt on the assumption that economic development would automatically mean improvements in women’s rights. In 2011, the All China Women’s Federation released the results of a large survey conducted alongside China’s bureau of statistics. In the section on gender attitudes, there were some encouraging findings: 83 percent agreed that women were just as capable as men, and 88 percent believed that men should shoulder some of the housework. 86 percent felt that there needed to be proactive moves to encourage gender equity.

But then, notably, 61 percent of men and 54 percent of women felt that “the field for men is in public and the domain for women is within the household.”

This result is particularly concerning when measured against the results of that question when it was asked ten years earlier. Compared to a decade earlier, 7.7 percent more men in 2011 believed that a woman’s place is in the home, and the number of women expressing that same view had increased by 4.4 percent.

As China’s population ages and society finds itself lacking in young labor—the one-child policy having already fallen by the wayside—it seems likely that pressures on women to give birth and care for the elderly will increase, with a corresponding impact on their earning potential.

One concluding thought to keep independent-minded Chinese women up late at night: will Chinese attitudes toward career-focused “leftover women” become more or less forgiving when jobs for men are scarcer and the economy demands more babies? The answer, hopefully, is not as simple as it sounds.

“Women’s Work” is the cover story from our 2016 issue, “Gender Equality.” Check out our subscription plans and discounts that will give you access to more great stories!