The problems with and solutions for China’s mental health worries

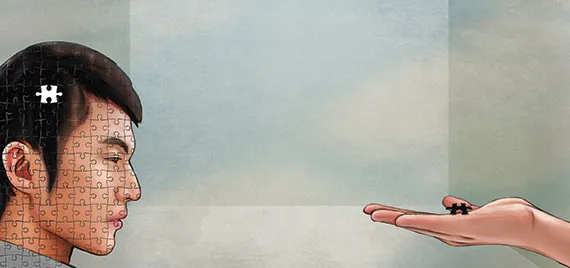

On the outside, sufferers are white-collar workers, college students, mothers abd fathers, and perhaps someone close to you. Mental health problems manifest in a number of ways, sometimes self-harm, depression, or an inability to work with or care for others. The worst pat about all of this is that it’s a disease no one can see, a problem people try to “get over” like it’s the flu. But, with China’s advances in so many field, the area of mental health care is woefully behind the times, and the authorities and sufferers know that it’s time to change both policy and minds. Some find themselves mired in an impossible public system or stuck in a toothless private alternative. Others are discovering that their diseases are nothing to be ashamed of; they’re something to be treated. And, still, others toil away in obscurity in a mental health care system that offers them low benefits and high danger. It may be treated like an issue that afflicts an unlucky few, but it’s a problem we all have to face.

FAILURES PRIVATE AND PUBLIC

People started waiting outside the Beijing Anding Hospital around six in the morning. Yue Gui, 30, sits on a suitcase with her son sleeping in her arms. She refuses to move and glares at the boy’s father who wants a smoke; the father tucks the cigarette back behind his ear.

The family came from Langfang, Hebei Province, less that 70 kilometers away from the capital. and it’s their second day waiting. They failed to register yesterday, so they came one hour earlier this time. “Our plan is to stay only for three days,” Yue says, concerned for her four-year-old son who rarely speaks ad keeps tearing out his hair. The father had his son’s head shaved, but the boy would still scratch his head until it bled. Wearing a knitted yellow hat made for him by his grandmother, the boy sleeps carefully and Yue lifts his hat to wipe away the sweat.

The local hospital in Langfang failed to provide a solution, simply giving the child some pills to keep him sedated. “Go see a psychiatrist in Beijing,” the doctor suggested.

The family soon learned that there are several famous mental hospitals in the capital and then quickly learned that all of them are crowded. “We picked the most famous one. We have to wait anyway.”

Under the haze of Beijing smog, Yue notices more people with suitcases—hoping to keep the cost of accommodation down as much as possible. Standing in the front of the row, she knows she’ll get registered today. “But I guess they won’t be able to make it,” she says, pointing to newcomers.

Beijing hospitals usually book 50 percent of appointment quotas online, reserved three weeks in advance, and keep open a certain number for clinic registration. The situation in Beijing’s other two mental hospitals, Peking University Sixth Hospital and Beijing Huilongguan Hospital, is similar. Visitors can be seen chewing bread for lunch and taking pre-dawn naps, leaning against the hospital lobby wall.

The government’s five-year plan on mental health (2015 – 2020) issued by the State Council this year states that the lack of mental health care services is at least partly due to a grave lack of psychiatrists in China. Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention data states that the country has over 100 million people who suffer mental disorders and 4.3 million severely mentally-impaired patients were officially recorded at the end of 2014, more than 55 percent of whom live in poverty.

But there are only 20,000 psychiatrists, all working in big hospitals in first-tier cities and provincial capitals.

“Problems caused by the shortage could have been solved if private mental health counselors were allowed to treat patients,” says Zhu Jianmin, head of the Psychological Department at Beijing Forestry University. In May 2013, China’s first mental health law took effect. Under the law, every mental illness diagnosis must be made by a “qualified psychiatrist”and private mental health counselors have no right to diagnose or give medical treatment regardless of qualifications.

Although many private counselors are still practicing, considered as a necessary approach worldwide to deal with mental health issues, patients reserve the right to sue if the counselors ever tell the patient they’re suffering from something as remedial as depression or attempt to treat them.

The five-year plan set a goal of managing more than 80 percent mental illnesses patients by 2020 and raise the number of doctors specializing in mental disorders to 40,000 by 2020, but the situation is complex. Without the assistance of private counselors, there won’t be enough doctors, even with 40,000 psychiatrists, and private counselors will be less willing to treat given the risks. As such, the whole process of private mental health care might find itself going underground, making the counseling industry more difficult to regulate and improve. While legality is certainly a problem, time, training, and money is what most stands in the way.

“The Brain In Pain” is a feature story from our newest issue, “Mental Health”, coming out soon. To read the whole piece, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.