War, huh, good god y’all, what is it good for?

In the modern tech age, if someone pushes the wrong button the world could come to an end. In fact this actually nearly happened in 1983, when Russian Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov was emphatically told by a computer that US nukes were flying his way. Fortunately he elected not to retaliate against what turned out to be sunspots and a malfunction, but that, as they say, is a story for another day. Still, we can be grateful that he didn’t set off another war, or 战争 (zhànzhēng).

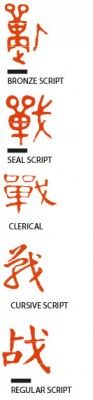

High-tech weapons, schemes, geopolitical, and social economic factors all come into play in modern conflicts, making them a dangerous business. By comparison, ancient wars seemed simple and almost innocent. Just look at the 战 character. In its traditional form 戰, the left represents its pronunciation and 戈 (gē) on the right side represents the shape of a weapon, a dagger with a long shaft. An alternative explanation of its origin states that the left side resembles a beast or 兽 (shòu) and together, the character means “to fight beasts with a weapon”.

High-tech weapons, schemes, geopolitical, and social economic factors all come into play in modern conflicts, making them a dangerous business. By comparison, ancient wars seemed simple and almost innocent. Just look at the 战 character. In its traditional form 戰, the left represents its pronunciation and 戈 (gē) on the right side represents the shape of a weapon, a dagger with a long shaft. An alternative explanation of its origin states that the left side resembles a beast or 兽 (shòu) and together, the character means “to fight beasts with a weapon”.

Just to give you an idea how straightforward war used to be, there was even war etiquettesome 3,000 years ago: you should send your enemy an invitation for combat and show up at the mutually agreed upon time and place, list all your troops, and conduct a religious ceremony before the fight commences. These were civilized attempts at mass-killing. You were not to attack your enemy state after their leaders died or were devastated by natural disasters, or your victory would be considered unjustified and dishonorable.

It was later during the Spring and Autumn period (770 BCE – 476 BCE) that war became an art of trickery and deceit, when different states frequently clashed and contested for supremacy. The military mastermind Sun Tzu was a product of this time and famously stated: “All warfare is based on deception.” (兵者,诡道也 。Bīng zhě, guǐ dào yě.)

It has basically been downhill ever since.

The character 戰 was later simplified into 战 . Its meaning is still straightforward in constituting a series of words and phrases. War is 战争 (zhànzhēng) while combat is 战斗 (zhàndòu). Soldiers are 战士 (zhànshī), and comrades who fight together are 战友 (zhànyǒu, literally “war friends”). You may find yourself in a skirmish and need several words for war: to declare war is 宣战 (xuānzhàn); while the fight is in progress, use the word 交战 (jiāozhàn, engage in combat). A temporary truce is 休战 (xiūzhàn), while a definitive cease fire is 停战 (tíngzhàn). When it comes to describing the results of war, you can either 战胜 (zhànshèng, win) or 战败 (zhànbài, lose). But the latter word is tricky in application; it could mean the opposite outcome when used differently. If there’s no object behind it, it means “lose” as in 他们战败了 (tāmen zhànbài le, they lost the war). However, in the presence of an object, as in 他们战败了敌人 (tāmen zhànbài le dírén), it means “they have beaten the enemy”. Tricky, huh?

We all wish for world peace, but who doesn’t enjoy the adrenaline rush of a harmless conflict? The closest thing? Sports! That’s probably why you find “war” words invading the sports page. A challenge is 挑战 (tiǎozhàn), and a record is 战绩 (zhànjì), for instance, 湖人队上个赛季战绩辉煌 (Húrénduì shàng gè sàijì zhànjì huīhuáng. The Lakers kept a great record last season). To prepare for a game, they claim they are “preparing for war” or 备战 (bèizhàn). Two teams going against each other? Use the term 对战 (duìzhàn), or “face each other in battle”. You just won your first game? Say 初战告捷 (chū zhàn gàojié), or “win the first combat”, and you will instantly feel like a noble general. 背水一战 (bèi shuǐ yí zhàn), literally “ fight with one’s back to the river”, describes a “fight or die” scenario. In sports, it’s the “win or out” match. Feeling even more dramatic than usual? Apply these words in your daily life.

Use 奋战 (fènzhàn) to mean “fight hard” for your college examination or an important project. 速战速决 (sù zhàn sù jué) is a military tactic, meaning “to attack and finish a battle quickly” as in a lightning war. But you can still use it in the most boring scenario to mean “to finish a task quickly”. For example, 我下午还有课,所以午饭必须速战速决了。( Wǒ xiàwǔ hái yǒu kè, suóyǐ wǔfàn bìxū sù zhàn sù jué le. I have a class this afternoon, so I have to have a quick lunch.)

“On The Character 战” is a story from our newest issue, “Military”. To read the whole piece, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.