A war for space in a drying rainforest

A primary school in Mansahao Village in Xishuangbanna, Yunnan Province is a whirlwind of activity; the school is moving to the town of Mengyang three kilometers away. The principle, Bai Yufang, beams with joy as she tends to the arrangements. Not only are they getting better classrooms, but they are also getting away from the fear and fatigue brought on by wild Asian elephants.

The school consists of a basketball court, a dormitory and two rows of ground floor houses that function as classrooms and offices. The campus has no walls and is surrounded by corn and banana fields. Last October, elephants hit the village for the first time in 10 years, walking right into the campus and strolling around the dormitory to get to the corn field.

In recent years, wild elephants have hurt and even killed people in other areas in Yunnan. Exhausted teachers had to stay up all night taking shifts to keep a large bonfire burning to keep the mammalian giants at bay, often with the help of the police and other villagers. Iron wire surrounds the bushes near the campus to fend them off, but they are useless in deterring the second largest terrestrial animal in the world, an animal hell-bent on the village’s entire crop. “Now that we are moving, the teachers can finally sleep at night,” Bai Yufang says, tired but smiling.

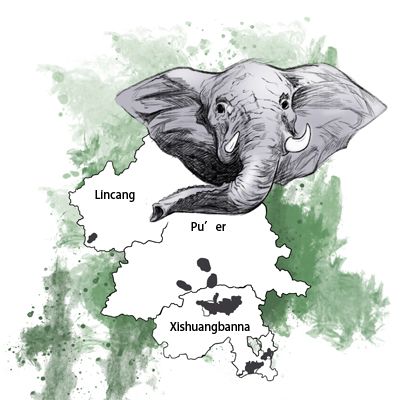

Yunnan is the only Chinese province where the Asian elephant still exists, home to around 250 Asian elephants, and Mansahao Village is located in the heart of one of the largest reservations, Mengyang. Three kilometers north of Mansahao is the famous tourist spot Wild Elephant Valley, which Mengyang is known for. There a dozen domesticated elephants there trained for circus work. While tourists flock to Wild Elephant Valley to watch the show and get photos while riding the great behemoths, they are often unaware that, just a few kilometers away, the wild elephants are captive in a different way.

Chang Zongbo is a 43-year-old forestry officer who has patrolled the Xishuangbanna rainforest for 20 years. His job is to protect wildlife and crackdown on the illegal animal trade, but, recently, his time has been occupied by elephant invasions, something that was not in his original job description. With his array of experience, Chang is a self-styled scholar on elephants, and though they often give him a great deal of trouble, he speaks of them as if they were good friends. “The herd of elephants hanging around Mengyang is made up of 14 members. You can easily recognize them because they are all smaller than average. In recent months there have been a few male elephants who were very nasty and attacked people a few times.” He also has insight on when they are more likely to harass the villages: “From February to May is the drought season, there is no water in the mountains, so they have to come down to the rivers to drink. In July they come down to eat corn, and in August and September they eat the rice. Also, in October, the male elephants fight for the right to mate—only the alpha male can mate with the females in the herd; the defeated males are driven out of the group. This is the most dangerous time because the spurned elephants are very aggressive. In October I’m always very nervous, because I know someone will get hurt.”

This means that Chang and his colleagues find themselves chasing elephants year-round. When villagers spot one of these massive animals, the first thing they do is call the emergency services at 110. “As forestry officials, we are not responsible for wildlife invasions, but they really need us. Think about it, they hide under the bed and shake when they call,” Chang says.

Authorities inspect a cornfield destroyed by hungry elephants.

The villagers usually make their panicked calls around midnight, because the elephants—ever the genius giants—stay in the mountains during the day and often descend into the villages when night falls. The police then chase them off with loud noises, using firecrackers, riot guns and even grenades. Using actual force with these animals would be dangerous to the elephant’s survival and possibly—due to their massive size—the survival of the perpetrator. “We are never very successful. They always come back,” Chang says. “In Africa, electric fences are very useful, but not here. You can’t put up electric fences in a rainforest.” Mansahao Village is not alone in its elephant invasions. In Yunnan Province, Asian elephants exist on five reservations, and the nearby villages are all affected to different degrees.

The situation is very different from a few decades ago. Although born a Xishuangbanna native, Chang never saw an elephant when he was a child. “There used to be a lot of elephants in Xishuangbanna, but their numbers declined drastically after New China. Some elephants were frightened into neighboring countries by dynamite when new roads were built through the forest and some elephants were killed in the 1960s and 1970s because there were no restrictions or laws forbidding their slaughter. When I first saw elephants, I noticed some of them had iron chains on their feet. Locals told me that it was because people used to trap them. It wasn’t until 1989 that I took my first snapshot of a family of wild elephants. Xinhua News Agency paid 1,000 RMB for the photo (a large sum at that time) because wild elephants were such a rare sight.”

Xishuangbanna is a Dai Ethnic Autonomous Prefecture, whose culture and language are affiliated with that of Laos and Thailand. In their traditional culture, the elephant is an extremely auspicious animal. In the mythology of the Dai, the Heavenly God created the world with 16 layers—so many layers in fact that the world was too wobbly. Thus, God made an elephant with clay and put the world on its back to keep the earth stable. On Dai festivals, the people play a drum called “Elephant Foot Drum” (象足鼓), which resembles an elephant’s foot.

In Mansahao Village, however, people have never heard of such legends. With the exception of a few elderly ladies in brightly-colored Dai skirts, the villagers just look like any other Han peasants. Thirty-five year old chairman of the village committee Ai Yi says: “We have no special reverence for elephants, nor do we hear tales related to elephants from the older generation.” He is dressed in a T-shirt, owns a smart phone and regularly uses WeChat. “At least, as far as I know, elephant worship doesn’t exist in Mengyang,” he added. The villagers meekly suffer the existence of these elephants. “We can do nothing,” says Lei Anqing, a villager whose house overlooks a corn field. “We have to just let them eat it all because they are just so huge.”

The village also doesn’t look much like a traditional Dai village, featuring bland concrete houses instead of the traditional bamboo cottages. “Nowadays, the villagers are richer than before, and they prefer concrete buildings which are safer to live in,” Ai Yi explains.

Although nearly every family plants corn and bananas, the plants that bring in the most income are rubber trees. People are aware that rubber trees—in terms of ecology—are disastrous. Rubber trees suck up to five times more water than a normal forest, with some in the area claiming that, if you plant a rubber farm by a river, the river will dry up. Yunnan Province is in its fourth consecutive year of drought; even the capital of Kunming has regular water shortage problems, and rubber plantations play a huge role in this. In the past 20 years, the extent of rubber farms has increased from one million mu (about 67 thousand hectares, 1 mu equals .07 hectare) to six million, and, to make matters worse, the price of rubber keeps rising. “The government wants to reduce the number of rubber plantations, but it’s impossible. Almost all the woods assigned to us have been planted with rubber,” says Ai Yi, pointing to the hills around Mansahao Village, which are smothered with rubber trees.

“Ten years ago, I was the chief of the police station. At that time, the area now covered with rubber and pineapples was still rainforest. So, the elephants stayed in what originally belonged to them,” Chang Zongbo says. “I grew up watching this place change. Originally, outside of the reservations, there was a broad-leaved forest; outside of the broad-leaved forest there were lunxiedi—swidden fields which would be returned to forest after three to seven years of farming. Now, the perimeter of the forest is entirely farms.”

Majestic Asian elephants graze in the rainforests of Yunnan.

Zhang Li is a life science professor at Beijing Normal University. He and his students have been monitoring Asian elephants in Yunnan Province since 1999. “We analyzed satellite photos from 1975 to 2005, and it shows that the elephants’ natural habitat was reduced from 5,000 square kilometers to 2,700 square kilometers, and it is largely because of rubber and tea plantations. With the forest becoming smaller and more fragmented, elephants have to adapt to the reality and find food in villages.” The growth of human villages and farms have completely cut off corridors that once connected different reservations, making it difficult for the elephants to migrate when they need to look for food in the dry seasons. On the other hand, in the villagers’ farms, the elephants can find sugar cane, pineapples and bananas by the acre and gorge themselves. “What’s better is that—in the wild—they have to go around all day long looking for food, but in the farms it is very easy for them to feast. They go and tell their brothers and sisters, and the family will stay around and harass the village for a long time,” Chang says.

and tea plantations. With the forest becoming smaller and more fragmented, elephants have to adapt to the reality and find food in villages.” The growth of human villages and farms have completely cut off corridors that once connected different reservations, making it difficult for the elephants to migrate when they need to look for food in the dry seasons. On the other hand, in the villagers’ farms, the elephants can find sugar cane, pineapples and bananas by the acre and gorge themselves. “What’s better is that—in the wild—they have to go around all day long looking for food, but in the farms it is very easy for them to feast. They go and tell their brothers and sisters, and the family will stay around and harass the village for a long time,” Chang says.

Hua Ning is the director of IFAW’s elephant protection project. Currently they are based in Pu’er (普洱), a reservation to the north of Xishuangbanna. “You can’t simply tell the villagers they should protect the elephants. Sometimes the peasants rely on the corn for their annual income. And then the elephants come and eat and trample their fields, leaving nothing for them to harvest. With their survival at stake, it is simply too much to ask for them to protect the elephants. When our project first started, we asked the villagers if they disliked the elephants, and they said they hated their guts. Our strategy is to tend to human welfare before we protect the elephants.”

One of IFAW’s solutions is to provide the villagers with micro loans and encourage them to plant things that are not food for elephants—such as tea, mushrooms and oranges—so that they can have something to sell if the elephants trample their corn crops. “It works. At the very least, it reduces the local resentment toward elephants. Today, when we ask the villagers what they think of the elephants, they are more likely to accept it as reality. They say, ‘What can I do? If they eat it, then let them eat.’” Hua Ning claims.

Planting tea instead of corn is also encouraged by the forest police, but Chang doesn’t think it will solve the problem in the long term. “It is very passive. When the elephants cannot find enough to eat, they will go to the next village.” Chang’s ideal solution is to let the elephants eat as they like. “There are only about six or seven villages along the paths that the elephants travel from one reservation to another. My opinion is to let the elephants eat their fill and to make the government compensate the loss.” He even has a specific figure in his mind that he considers reasonable: “We know the normal harvest of a mu, and the government can compensate based on that, and perhaps even pay about 10-20 percent lower than market price.” This is certainly possible, what with local governments getting more subsidies for elephant reservations. The real problem is that they may not be willing to spend it on helping the villagers and elephants live in harmony.

Elephants mill around the concrete homes of frightened villagers.

For the villagers of Mansahao, neither way is an answer for the near future; they rely on China Pacific Insurance, which will supposedly compensate 400-500 RMB per mu for crops destroyed by elephants. Even though this is less than one third of what the villagers spent per mu, the villagers haven’t seen a penny from them yet. “Every time the elephants come, people from the insurance company come and rate our loss, but half a year has passed and none of the villagers have received any compensation,” Yan Yi claims. “I haven’t heard of anyone from any other villages getting their money either.”

As for next year, the villagers aren’t considering changing their crop. When asked, they invariably answered that they will continue to plant corn. This was, after all, the first time the elephants had invaded in 10 years, and the villagers hope they don’t come back. The elephants, with their usual class and poise, declined to comment.